Most of the time, they just look like turds.

Which they are not, of course. Colloquially known as sea cucumbers, they are holothurians, a class of echinoderms, which are marine animals characterised by tough outer skins and radial symmetry. Think starfishes, or brittlestars, or urchins. All relatives of sea cucumbers.

Sea cucumbers inhabit most, if not all, of the world’s ocean bottoms, from waters shallow enough for you to wade in, to the deepest, darkest corners of the sea. They do move, but usually not at a pace that is of interest to the casual human observer.

Like I said, turds.

Divers sometimes take note of sea cucumbers because other animals live on and in some certain species—colourful commensal shrimps for example, and even a type of fish called pearlfish (Carapidae) that often homesteads in the rear end of sea cucumbers. Yes, the turd-end of the turd. I kid you not. Look it up.

In general though, these animals do not get a lot of love (except maybe when they are over-harvested for food). Which is a shame, especially when they themselves are in an amorous mood.

At certain times, they lift themselves up from the substrate to engage in broadcast spawning, swinging to-and-fro, swaying in circles, gyrating to a timeless rhythm only they can sense.

This one was male (Bohadschia argus). Females do the same. Ideally, individuals within a given vicinity do this at the same time in order to maximise chances that gametes meet to make baby turds (which, come to think of it, must be adorable).

Most of the time, they just look like zits. Corrugated pimples on rocks.

Which they are not, of course. Limpets are aquatic snails characterised by conical shells. Each has a strong muscular foot, which acts as a suction cup, giving these volcano-esque gastropods the ability to adhere to rocks and other hard surfaces. Which is important, because these shells tend to live in the intertidal zone. This means getting pushed around by tidal flow, as well as being buffeted by waves and swells.

I should note that a number of different genetic lines comprise what we colloquially call limpets. They are—to use a fancy word—polyphletic, i.e., descended from different ancestors. Over time, the various lineages have arrived at a similar morphology and ecological niche.

Divers rarely take note of limpets.

In part, this is because divers usually don’t spend much time in the intertidal zone. But also…zits. C’mon, who wants to be reminded of one’s be-acned teenage years?

Like sea cucumbers though, these animals are mobile. Again, not at a pace that is going to thrill most people. I have stared at limpets for over an hour at a time, during which I think that I might possibly have noticed some potential motion. I am exaggerating somewhat for emphasis.

Limpets do sometimes move at a detectable pace, such as when they graze. The snails use their radulas (sort of a tongue with teeth) to scrape algae off the rocks. Vegetarian zits.

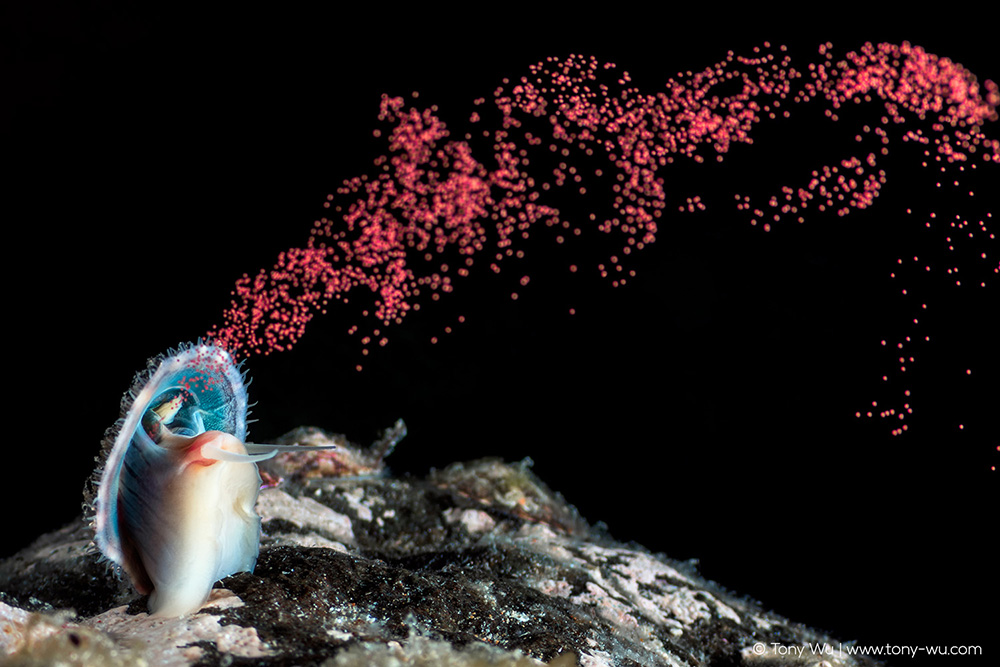

Again, as with sea cucumbers, these animals don’t get a lot of love. Which is a shame, because they too can put on a show when they’re in the mood for invertebrate intimacy.

This one is a female Lottia emydia sending forth a stream of eggs. Other individuals in the area synchronise their spawning activity to roughly the same time, saturating the area with gametes. Yes—you guessed it—in order to make little zits.

Most of the time, they just look like butt cracks (I make optimal use of my puerile vocabulary, doncha’ think?).

Which they are not, of course.

I’m talking about bivalve molluscs, specifically sessile ones, meaning ones that do not move, at least not after they’ve settled and matured.

Some bivalves can move. Many divers, for instance, have seen scallops flitting through the water—clap, fyuu, clap, fyuu, clap, fyuu. (If you have a better onomatopoeic term to suggest a scallop swimming through the water, please let me know.) Others burrow into sediment, sifting through sand, mud and rubble in the process.

The butt-crack species though, are the ones I’m concerned with here. The ones that adhere to surfaces or excavate into rocks and coral, locking themselves into position. Often the only thing one sees—if one notices these animals at all—is an elongated, sometimes jagged, dark crevice.

There isn’t a lot more that I can tell you about such bivalves. Except that they too, like the sea cucumbers and limpets I discussed above, do not receive much attention. And they too are capable of putting on quite a show when it’s time to procreate.

The photo below shows a female bivalve that has burrowed so far into the rock/ coral that it is almost completely concealed. I have no clue what species it is. The strands of orange goo comprise eggs, millions of them, squirted out in less than the blink of an eye. Like if you were to Hulk-Smash! a tube that happened to be filled with orange toothpaste.

Look carefully and you can just make out a damselfish (Pomacentrus nagasakiensis) in the background. Trying to predict when and where which hidden bivalve is going to gush gametes is challenging, to say the least. Yet somehow, these fish know exactly when to be where in order to gorge on a fresh omelette.

These animals all have one thing in common. They comprise what I’ve come to call “The Other 99%,” meaning those organisms that are not flashy, cute or charismatic enough for posters, stuffed animals, NGO fund-raising campaigns, and such. As a result, they receive almost no attention.

Pretty much zip.

Even though they may not pique most people’s interest, the reality is that unassuming animals like these are vital to health of the oceans, and thus by extension, to us. Our lives are intertwined with theirs.

Think of sea cucumbers as elongated Roombas, moving along the ocean floor hoovering up stuff, changing direction when they bump into something. Picture limpets as smaller, slower Roombas, specialising in the polishing of rocks and other hard surfaces in shallow water. Sessile bivalves then would be motion-challenged Roombas. They filter water, taking out organic material, removing pollutants as well.

In short, sea cucumbers, limpets, sessile bivalves and many other uncelebrated organisms purify the seas. They gather, consume, and recycle organic materials. They keep the marine environment clean. They keep oceans healthy.

We depend upon the ocean for food (an average of about 20kg/ person/ year, though this varies by nation). We visit the sea for recreation. We utilise the sea for raw materials, transportation and energy. My point being that our very existence depends upon having healthy seas, which are maintained by under-appreciated essential workers like these.

Which brings me to my final example, the star of this newsletter (forgive the pun), this spawning starfish (Leiaster leachi):

This image is the winner of the Underwater category in the 58th Wildlife Photographer of the Year contest (#WPY58). (Read my blog post. Even better, sign up to read blog posts by email here.) This image was also a finalist in the 2022 Big Picture Natural World Photography competition.

The biggest reason I am happy about the awards is that the juries saw fit to shine the spotlight on a member of The Other 99%. Sure, more people recognise starfishes than limpets. But they are still largely ignored, taken for granted (one exception being starfishes dried out and sold as tourist trinkets—please never buy those).

When things went wonky in early 2020, instead of obsessing about what was no longer possible, I immediately focused on new opportunities. I pivoted from photographing whales to working on a new project—documenting Japan’s oceans, with a particular emphasis on organisms that are mostly overlooked or ignored.

The photos above are a few examples. There are more, and hopefully many more to come.

I will be pursuing The Other 99% for the foreseeable future.

I have seen and learned much. I have had the pleasure of meeting wonderful people, coming to call many friend. And I have derived tremendous satisfaction from applying the knowledge and experience that the ocean has shared with me over the years to calling attention to the forgotten ones, the unsung, the un-loved.

There is magic in all life. We just have to pay attention.