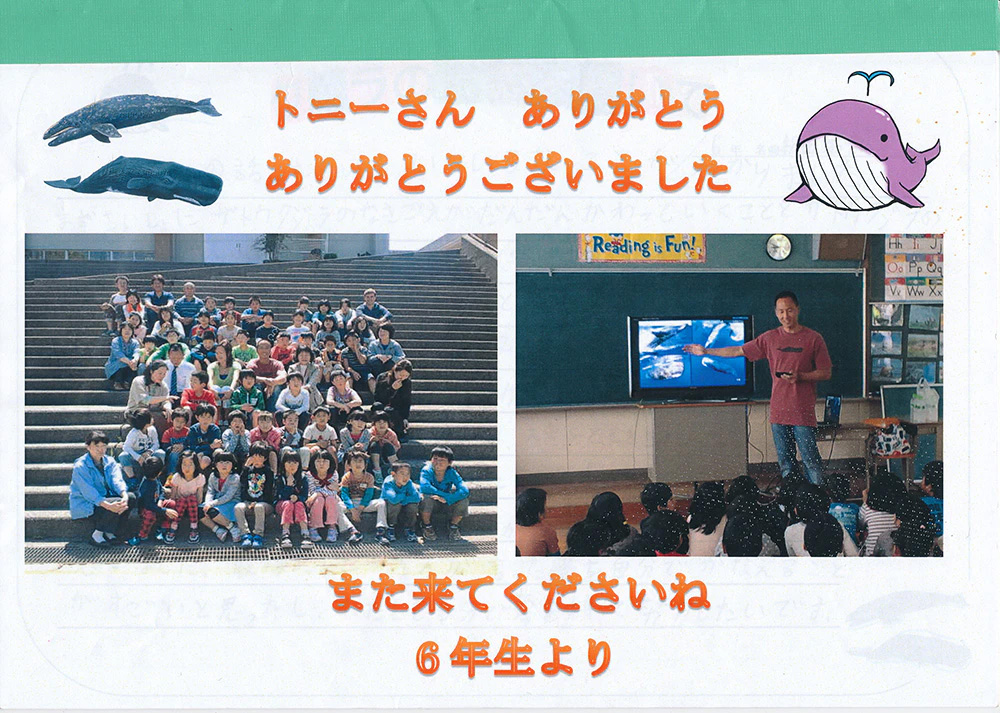

It was May 2015. I found myself once again in Kannoura, a small town in rural Japan, standing in front of several dozen kids, ranging in age from six to twelve. My young audience was seated on the floor, expressions eager, faces expectant. Some smiled, a few giggled. One even pointed. There was a slight murmur. Nothing impolite, just run-of-the-mill chatter. Most of them remembered me. I was, after all, an oddity.

This story actually started with a drink, as many tales do. Said drink was imbibed (with a substantial number of additional drinks if I’m to be entirely honest) two-and-a-half years prior, in a restaurant in Osaka, the name and location of which I don’t entirely recall, due—without question—to the aforementioned plethora of drinks.

I had just finished giving a presentation to a group of divers. The event that had been arranged jointly by a store specializing in equipment for underwater photography and a manufacturer of camera housings.

My topic for the evening was whales, so that was easy. I had given my talk entirely in Japanese, so that wasn’t quite as easy. It had, in fact, been the first time that I’d ever subjected actual humans to the sound of my voice for 120 minutes in Japanese, non-stop nonetheless.

Which explains why everyone needed drinks.

One refreshment led to another, and I found myself staring at an iPhone. Not a random one of course, but a phone that had been placed in front of me with a video running. The fellow holding the iPhone was talking, quite a lot and a bit rapidly for my impaired level of comprehension at the time, so for the most part, I smiled and nodded, doing my best to effect an expression that conveyed appropriate measures of appreciation and interest.

I actually just wanted to sleep.

Perhaps it was not the most auspicious beginning to a friendship, but as it turned out, the guy with the iPhone and I would end up becoming the best of friends. His name is Nori, short for Norihiro.

The details of how exactly this came to pass aren’t terribly pertinent to the point that I want to convey in this newsletter, but the fast-forward version goes something like: go home, decipher notes scribbled while inebriated, research subject matter, experience the thrill of unexpected discovery, engage in follow-up communication with Nori, design and get made custom equipment, confront seemingly insurmountable technical difficulties (crucial to all nature documentaries), travel to location, experience delays followed by disaster and failure (also crucial for any made-for-TV documentary), culminating in sweet victory(!) in May 2014, complete with first-ever high quality photos of Chiloscyllium plagiosum sharks mating in the wild, massive display of fireworks when I emerged alone from the ocean that night (really), a humongous feast and of course, copious alcohol (it’s Japan, after all).

Nori lives in Kannoura, which is in Kochi Prefecture, part of Shikoku, the smallest of the four main islands that comprise the backbone of the Japanese archipelago. It is a quiet, rural area. Ocean breezes and tree-covered mountains keep the air clean and water pure. It is a place where dragonflies still patrol the skies and tadpoles swirl in rice paddies, where everyone knows everyone. The population is not big, around 500 residents. The average age is north of 60, maybe even 70, typical of many outlying communities in present-day Japan.

At one point, the area was a booming tourist destination. That was during the heyday of the financial bubble in the 1980s. People from the nearby urban center of Osaka would visit on weekends and holidays—flush with cash—to sit on the beach, eat, drink, make the most of the good times.

That ended with the crash.

A dilapidated and rusting ferry terminal dominates one edge of the harbor. A solid hit by a powerful typhoon would collapse much of what remains. It is a visual reminder of glory days gone by, much as the fossilized skeleton of a T. Rex recalls the heyday of the Cretaceous.

Today, there is no industry in Kannoura, no commerce per se, minimal tourism. There are fishermen, farmers too. Surfers visit the area when the waves are up. Otherwise, it is a place that is most notable for escaping attention.

During my initial visit, I struck up a chat with a boy who had accompanied his father to Nori’s house for dinner. Young Taketo was 10 years old at the time. He wanted to know what I do. I showed him photos, shared stories and answered questions. We spent the entire evening together.

The next day, I found myself at the Kannoura Elementary School. Izumi-san, the Headmaster, had asked Taketo’s father to ask Nori to take me in to see her.

So there I was, sitting in her office.

It is amazing how much a school Principal’s office feels like a school Principal’s office, irrespective of the country. I found myself fidgeting, nervous no doubt because of some subconscious recollection of the times during school when I had been called into the Headmaster’s office. Those experiences never went well.

Izumi-san offered us green tea, smiled. Apparently, Taketo had charged into her office that morning, relating everything he could remember from our conversation the night before.

Izumi-san, as I would later come to appreciate, is a person who far exceeds expectations for the head of a school in rural Japan. Physically, she is petite, standing just over 1.5m (around 5ft). She was a few years from retirement when we met. In demeanor, she is inquisitive, engaging, and ever-optimistic.

She fired questions at me as rapidly as I could answer. Sometimes faster, so that I had to double-up on the pace of my replies. She was never rude, just genuinely interested.

Not surprisingly, the kids loved her. Yes, love is the correct term. They respected her, of course. They listened to everything she said, but there was a deeper connection there, something more akin to family. After class for example, they poured into her office to chat with her and gawk at me, probably more the latter in this case, but it was abundantly clear that they enjoyed Izumi-san’s company. Vice versa as well.

When the room finally cleared, she asked if I would consider giving a talk for the kids.

How could I refuse?

“How long of a talk?” I asked.

“Let’s do half a school day, from 08:20 to 11:30.” She replied.

Gulp.

I pulled an all-nighter preparing and rehearsing a presentation. Though I had given several more talks in Japanese since that inebriated night in Osaka, this was to be the longest to date, with the toughest possible audience no less—kids.

Fortunately, the morning went really well. Kids sung along with humpbacks (OMG that was so adorable), oooh-ed and aaah-ed at the translucence of sperm whale skin, snickered at the sight of whale poop. The concept of a whale fart induced hysterics.

My juvenile sense of humor was not for naught.

Best of all, after three hours, when I started to ask if there were any questions, the kids leapt off the floor like popcorn off a hot skillet, hands raised, questions bursting forth.

Circling back to the scene I described at the beginning, this was now my second time at the school, a year later, again in May. At the recommendation of Nori, the prefectural government had invited me back to address to the general public on the occasion of the opening of a new tourism facility.

I realized that a second visit would give me another chance with the kids.

The year before, after telling them about whales, I had left them with one final thought.

Kannoura is a community that faces many challenges. As I described above, it has seen better days. Putting myself in the position of the little ones, I imagined what it must be like to grow up in a town where new, exciting things come along only rarely and opportunities seem scarce. It did not escape my attention that I had a chance to make a difference in their lives.

Once the questions were answered and it was almost time to break for lunch, I told them that my talk that day had not been about whales. Not at all. Not even about photography.

Cue befuddled expressions.

I described my own background, told them how I was supposed to be a doctor, how I had broken family expectation to become a banker, how I had learned Japanese, how I had worked myself up from having and knowing next-to-nothing to standing in front of them sharing stories. I also described some of the tough periods I had faced, admitted that I had failed—miserably at that—many times.

I concluded with, “The photos I shared with you today, the stories I told you, those were all a result of pursuing my dreams. Having dreams and pursuing them with everything you’ve got, and not giving up when things don’t go your way, is the most important thing in life. If you remember nothing else from today, please remember this one thing. This is the reason that I came to share the morning with you today.”

A couple of weeks later, I received a package. It was filled with letters and drawings from the kids, each describing his/ her aspirations, dreams, hopes in life. Letters from the younger kids were cute. The ones from the older students contained more substantial thoughts and emotions, details of actual ambitions.

I read each one. Tried—but failed—not to cry.

As I stood in front of the kids again, I knew I had to sneak in another life lesson, something more meaningful than just “hey, look at these pretty pictures.”

We embarked on a tour, a rapid-fire trek around the oceans of the world. We started in the tropics with pictures of coral reefs brimming with color and life, moved on to stranger things in dark mucky environments, then to went to play with bigger animals like sea lions and cetaceans. We visited Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Australia, Tonga, Sri Lanka, and Palau.

Toward the end, I said, “I have a few more photos to share with you today. I took these pictures in one of the most beautiful places that I ever have had a chance to visit. I want you to guess where these photos are from.”

That piqued their interest.

First was a photo of seawater swirling around volcanic rocks on a pristine beach, dramatic storm clouds above. Next was an ethereal coastal seascape illuminated by the cool light of a magnificent full moon. Then came images of crystal-clear water flowing in, around and over time-worn boulders in a mountain stream.

No guesses yet.

Birds in flight. Frogs in trees. Frogs in water even. It wasn’t until I showed them a photo of a fire-bellied newt that one of the older boys blurted out, “It’s here! It’s here! The photos are from here!”

The kids started grabbing one another, some saying: “Wait a second, I know where that is!” while others exclaimed, “Wait a second, I’ve never seen that!” It was several minutes before I could talk again, such was the enthusiasm.

To prepare for the talk, I had spent two weeks exploring every nook and cranny of their community, looking for interesting things to learn about and photograph. I had enlisted the help of (very patient) friends, woken up before dawn to walk the coast, driven high up into the mountains to explore rivers and streams. Behaved, in other words, like a kid sans adult supervision.

Once the chatter subsided, I shared two final photos with them.

The first was this photo of a soft, fluffy dandelion, set against a background of verdant green.

The second was the following photo, again of a dandelion. Compared to the first image, this one feels stark. The background is dark, seeds and stems straight and hard.

It is the same dandelion. I took the pictures only a few minutes apart, in a patch of grass next to Nori’s house.

I explained to the kids that much of how you perceive things, what you feel as a result, depends on how you look at them. The dandelion, for instance, didn’t change. How I looked at the flower is what made one photo different from the other. Soft vs. hard. Delicate vs. rugged. Bright vs. dark.

My point to them was that in a similar way, how they look at what is around them makes a big difference in what they see, and thus, what they feel.

“You know that I have traveled around the world to see many places and meet many amazing animals. But do you know how much fun I had meeting the animals and seeing the beautiful things that you have right here? Do you know how much I learned? Do you know how lucky you are to have so much beauty here?”

There was silence. The good kind. The kids looked at one another. The adults in the room too. I let that thought sit for a while, then wrapped up.

Though few that day may have realised it, I chose the dandelion seeds for a reason. For it was, in a way, seeds that I tried to plant that day. Metaphorical ones of course.

In all likelihood, I will never know if the seeds I sowed found a comfortable place to settle, to germinate and take root, one day to flower and develop into something of breathtaking beauty.

But isn’t that the nature of all seeds, in the wild at least? Many must be planted for a few to take hold and transform the world.

ars gratia scientiae