This is a female East Asian octopus (Octopus sinensis). She is a member of a species that is quite common throughout Asia, one that was lumped into the generic moniker of common octopus (Octopus vulgaris) until 2016. (1)

There is in fact, not much remarkable about Octopus sinensis, once you get past the generic wow! factor of octopuses in general—blue blood, three hearts, distributed neural network, high intelligence, individual personality, shape-shifting skin, etc. Did I mention chromatophores?!

What made this one special is the mass of eggs behind her.

The Japanese name for this species is madako (マダコ), pronounced ma-dako. Like many other inhabitants of temperate waters, these octopuses coordinate their reproductive season. Having mature octopuses in a given area all get in-the-mood at roughly the same time increases the number of potential partners and the odds of a successful hook-up. Timing of reproduction in temperate conditions is influenced by ambient conditions as well—temperature, currents, food supply and such.

For madako, the ideal time seems to be in the summer months, running into autumn. That is when this species reproduces, at least in Japanese waters.

This female chose winter.

The photo above is from 7 February 2021. She was first spotted with her clutch of eggs on 23 December 2020 by my friend Toida-san.

As you might imagine, a good mother octopus wants to protect her brood. She made her den at the end of a small ravine between large rocks, a ditch that I could just squeeze myself into. At the far end of the dead-end ditch, she was another 50cm or so further back in a small, dark tunnel, one that dipped down at first, then went back up. To see her clearly, I had to lie prone at a downward angle of 10-15º or so, then crane my head to look up—cue appointment with chiropractor.

She had selected a place that was easy to defend—an excellent strategy for her; less-than-ideal for me. Not only was the V-shape access awkward, but the ratio of camera+stuff size to den aperture was suboptimal, to say the least.

I managed to contort myself and gear into the correct position only once. She was relatively forward in her den that day and didn’t seem to mind the fiddling and futzing. I got everything to fit by disassembling it all and wedging bits and pieces among the rocks, trying not to knock things off-kilter each time I moved. I kinda think the octopus might’ve been mildly amused by what the appendage-challenged idiot outside her den was doing.

I went to visit the octopus several more times after that, but refrained from trying to photograph her again. Having a female madako successfully bring a clutch of eggs to term during the winter is probably not a common thing, at least as far as I know. I figured that as the eggs matured and the potential for hatching grew closer, the less disturbance the better.

It was possible to use a small point-and-shoot camera to record her progress though, which is what Toida-san did.

We figured it was important to keep a record, to document the outcome, whatever it might be.

There had actually been another female with eggs in January, just a few metres away. That female’s eggs had appeared dull and deflated from the get-go though. Picture flaccid balloons, drab to boot.

That second female disappeared a few days after I saw her. There is no way to know for certain what happened—but the eggs were gone, and she was nowhere to be seen.

The fact that there had been two female octopuses with eggs in the same area during a time of year when this species doesn’t normally reproduce made me even more determined to keep track of this one.

Why did she have eggs now? Why were there two in the same area? If her eggs hatch, will they survive? And if they do, how will they cope with being off-cycle with peers?

In case you’re wondering, the water temperature throughout the observation period fluctuated between 14ºC and 16ºC, tending toward 16ºC (about 61ºF) on most days. That was, according to Toida-san, perhaps a little warmer than in previous years, but not particularly unusual.

Without accurate long-term records from this exact location, it is difficult to know if temperature was a factor. I am tempted to think that it was, as I have seen and experienced a number of other odd marine phenomena in recent years, but I am also wary of jumping to conclusions or making unsubstantiated statements.

Speculation is good, because that’s how you foster creative thinking and come up with interesting ideas. Making claims one can’t support with hard data is not though, because that’s how we end up with misunderstandings and outright falsehoods.

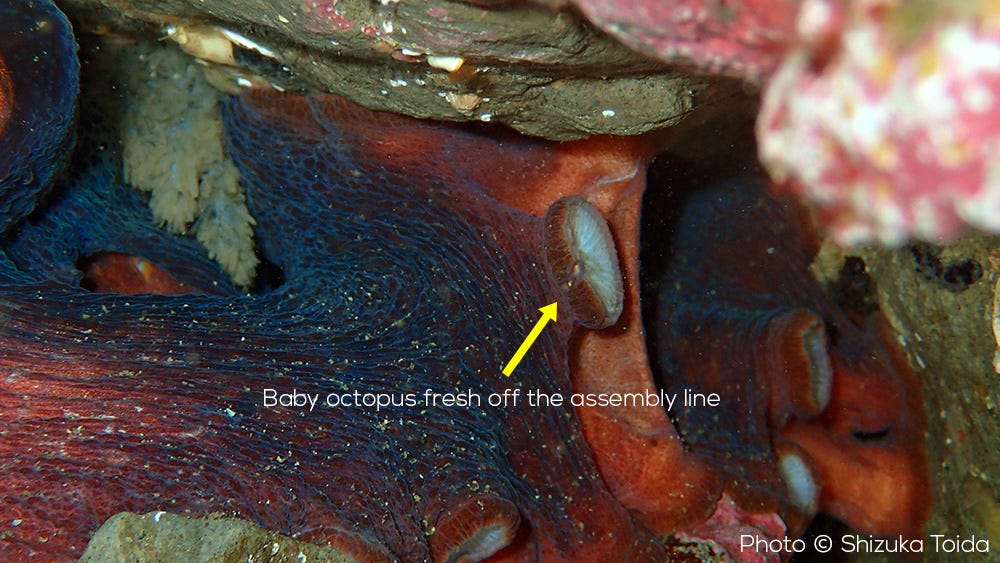

During her daily check on 2 March, Toida-san noticed that some of the egg casings seemed to be empty—a sign, perhaps, that a few of the babies had hatched. It is normal for juvenile madako to mature a few at a time. But we had to see an actual baby in order to be sure.

Fortunately, that happened on 8 March, when Toida-san was able to witness and document the moment that one of the tiny cephalopods ventured forth.

Each day, more babies matured and hatched. By 12 March most, if not all, of the baby octopuses were gone, as you can see from the following photograph:

On the one hand, we were delighted. Mommy madako had beaten the odds. She had nurtured a large clutch of eggs during the winter!

But there was a flip side.

Madako mothers die after their eggs hatch.

I had known this of course. It is normal among coastal octopuses. But somehow, I hadn’t thought about it during the weeks that we had monitored and observed her. I think the same was true for Toida-san. We had been completely focused on the eggs.

It wasn’t until all the babies had hatched that reality hit. I was away in another part of Japan for a project at the time. We exchanged messages that went something like this:

“All the eggs hatched. Hurray!”

“This is so incredible. I’m so happy. She did it!”

“It’s still winter. What do you think will happen to her?”

“I don’t know.”

“You know they’re supposed to die?”

“Yes. I know it’s probably going to happen. I don’t want it to happen. I might cry.”

“I get it. Me too.”

So we prepared.

A week passed. She looked healthy and strong.

Another week passed. Still alert. Still looking good.

Another week. The same.

My impression was that octopuses perish within a short time after all their eggs hatch. By this point, the end of March, she would most likely not have eaten anything for over three months. And she had been hard at work for most of that duration protecting and nurturing her eggs.

Our message thread continued:

“This is amazing. She is still looking quite healthy.”

“I checked with friends in other parts of Japan. The octopuses normally die quite soon after the eggs hatch.”

“Do you think it’s possible she might survive?”

“You mean until the normal breeding season? That would be incredible! From the photos, it seems like a possibility, but then again, she probably hasn’t eaten anything. I don’t understand how she’s survived for so long.”

“I don’t want her to die.”

“Me neither.”

So we waited. Toida-san sent me daily updates.

Our octopus did reasonably well through the first part of April. Some signs of decay had appeared in her body, but she was alert and active.

We held out hope.

But when Toida-san visited on 10 April, this is what she saw:

Our octopus was dying. She was still alive, but scavengers (gastropods) had already started to consume her flesh.

By 12 April—one month after all her eggs had hatched—our octopus was gone, nowhere to be seen.

The messages we exchanged that day were sad—virtual tears that I am certain would have been real ones had we been in the same place together.

Our octopus—mommy madako—who had been out of sync with her reproductive cycle, was finally out of time.

ars gratia scientiae

Timeline:

23 December 2020 - First spotted with eggs

2 March 2021 - First eggs started to hatch

8 March 2021 - Confirmed visual of baby octopus hatching

12 March 2021 - All eggs hatched

10 April 2021- Significant body decay; scavengers consuming flesh

12 April 2021 - Octopus gone

Notes:

(1) Gleadall, Ian. (2016). Octopus sinensis d'Orbigny, 1841 (Cephalopoda: Octopodidae): Valid Species Name for the Commercially Valuable East Asian Common Octopus. Species Diversity. 21. 31-42. 10.12782/sd.21.1.031.