Kevin did not show up this year.

That pretty much sums up 2023.

Oceans—around Japan at least—have been disturbed. Currents have changed. Temperatures have been off. Behavioural patterns have shifted. Species have appeared or disappeared. Things have been, in a word, askew.

My best-laid plans for the year went awry more often that not. Reproduction happened weeks before I got to location. Reproduction seemed never to have happened at all in other instances. And for the first time ever, I cut my losses and departed a location early, once it became clear that winds, weather and water would not cooperate for the then-foreseeable weeks into the future.

On a personal front, the year has been one marked by loss, sorrow and anxiety. Not so much for me directly, but for people I know and care about, people who make my life richer and the world a better place. People who deserve(d) better.

In many ways, 2023 sucked.

I pen my thoughts as we say goodbye to the year not with the intent to wallow though.

I write with a sense of gratitude.

For despite adversity, despite having so many things go sideways, there have been moments—extraordinary ones made that-much-more special by juxtaposition with tribulation.

In the spirit of focusing on the half of the glass that is full, I’d like to share a sample of the incredible things Mother Nature has shown me in the past twelve months, with the hope that you will view them with the same sense of fascination, wonder and appreciation that I do.

The title of this newsletter is Gratitude.

Let me start with Kevin, the charismatic fat greenling (Hexagrammos otakii) that featured in a previous newsletter titled Wonder Women.

After a three-year interlude, I managed to make my way to Hokkaido once again in search of my finned friend. Since I wrote about him and his kin in 2020, Kevin has returned each season to claim his rock, don his finest to woo the girls, say hello to humans when it suits his fancy.

He was not spotted this year. I use the passive voice intentionally, first to underscore that I am not the only person keeping an eye out for him. And second, to convey that just because no one saw him doesn’t mean he wasn’t around. Male greenlings don’t necessarily have to pick the same spots to set up house each season, though Kevin had done so for many years.

Circumstances dictated that I could only get to Kevin-territory late in the year, a few weeks past the time when male greenlings usually turn on their yellow charm for the girls. As it happened, the greenlings were two to three weeks late with their reproductive season.

The oceans have been wacky of late. Recent months seem to have witnessed greater deviation from mean conditions than at any time in memory. This is not just my recollection, but the opinions of friends who have dived the same areas continually for a decade or more (over 30 years in one instance).

This year’s greenling delay worked out well for me. It meant that I had an opportunity to witness something for the first time—the emerging of baby Kevins into the world.

Birth is a privilege to witness—that moment when inorganic materials combine to become a living being. There is no greater magic.

Photographing the birth of a fish like this poses multiple challenges. The water is cold—around 10ºC (50ºF) at the time. The eggs are small—around 3mm (0.12in), with unfurled babies measuring about 7mm (0.27in). Baby fishes are fast. We used video to clock the time for two hatchlings coming out of their eggs. One was just under 1 second; the other just over a second. By “just under/ over,” I’m talking milliseconds.

In practical terms, this meant using a 4x life-size magnification diopter to look for the right egg at the right time, trying to find and lock focus upon subjects that twist-twirl-pop at random, all while while being pushed around by current and swell.

Crazy. Stupid. Frustration.

Not quite as small, but equally frustrating were copperstriped cardinalfishes (Ostorhinchus holotaenia). An adult male, about 3cm (1.2in) in size, spits thousands of teeny-tiny babies out of his mouth to give birth. Sounds simple and straightforward, right?

The catch is that males do this while swimming at high speed in erratic start-and-stop zigzags, in total darkness. There is variation in timing, so it’s not like you can say, “Right, it is X o’clock so it’s time.” It’s more like, “The sun is down. Swim around mostly blind and hope to find a fish that appears as if he wants to jettison cargo while you still have enough air to hang around.”

Moreover, they don’t care for light. So if you shine a light on them to see, they won’t cooperate.

Each papa fish has his own personality. Some swim a lot and take their time. Others spit everything out right away and wipe their fins of the entire affair. Some are shy. Some are bold. Most seem to know to face away from your lens. Some particularly clever ones charge straight at your lens while launching shiny countermeasures, just to screw with autofocus.

Easier on my cortisol levels was photographing this Epiactis japonica anemone with its babies:

No one would fault you for thinking that squiggly-appendaged invertebrates don’t attend to their progeny, but this is photographic proof that some do. The parent (the one with the blue mohawk) makes a crease in its base before depositing baby anemones into the resulting fold.

In science-speak: “a normally flattened anemone contorts itself into a dome shape; it bends its column, producing a fold; the mouth protrudes in the direction of the bend; zygotes or early embryos are released through the mouth directly into the fold. During deposition, the mouth moves in a circle depositing offspring as it revolves around the animal. The groove may partially or fully cover the offspring at the time of deposition, but later in the brooding season, the groove disappears and the juveniles are exposed upon the surface of the adult.”(1)

My understanding is that mini-anemones live rent-free until they’re old enough to move out, or the parent gets sick of the freeloading and kicks juniors to the curb.

One minor victory this year had to do with molluscs. Last year, I photographed females of two mollusc species broadcast spawning colourful eggs—the limpet Lottia emydia and top shell Tegula pfeifferi. The red and green egg colours made for a nice holiday-themed year-end greeting graphic:

This year, it was the boys’ turn:

I didn’t set out to photograph females first, males second. It just turned out that way. I was delighted to be able to document males of these two species—to complete the set, so to speak. The Lottia male was kind enough to spawn during daylight hours. The Tegula however did his thing at 3:57AM. There were remarkably few people around at that time.

If you know what you’re looking at, you can see eyes of both boys (yes, they have eyes!). The Lottia eye is easier to distinguish. The Tegula is more obscure and smaller in the frame. If you need help to find the eyes, perhaps consider consulting your local malacologist (yeah, that’s a new word for me too).

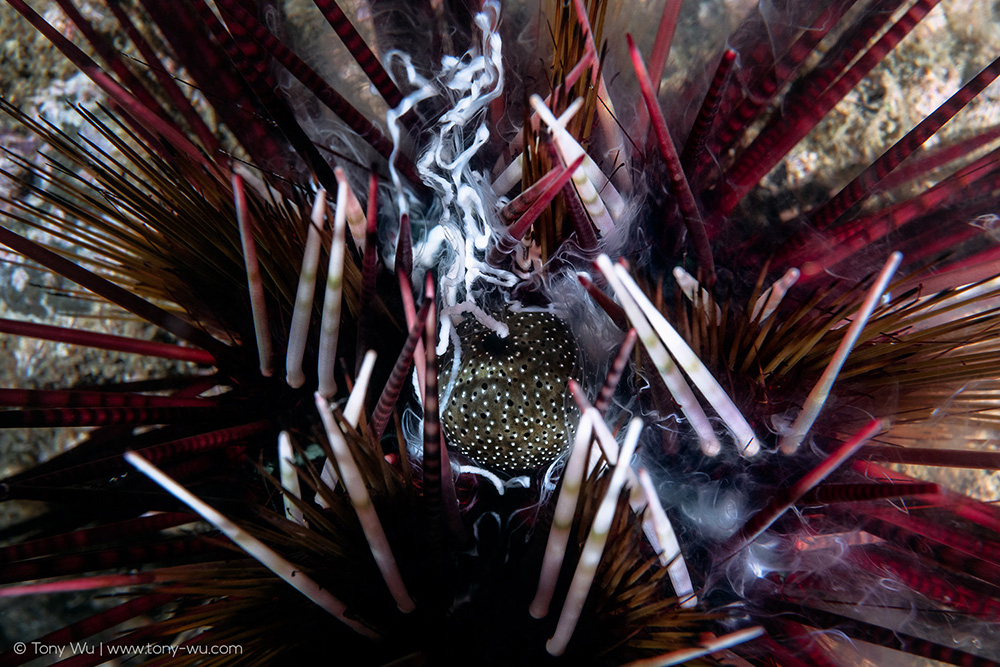

While I’m on the topic of invertebrates overlooked by normal, well-adjusted divers, here is a close-up of a male Holothuria (mertensiothuria) leucospilota sea cucumber broadcast spawning:

Sea cucumbers elevate the front portions of their bodies and sway back-and-forth, round-and-round in a hypnotic manner while engaged in spawning. The motion is slow but unpredictable. This one was in extremely shallow water, maybe 3m (just < 10ft), but there were large, erratic swells to exacerbate visual vertigo.

In contrast, Japanese sea biscuits (Clypeaster japonicus), which are a type of urchin, are mostly stationary during spawning.

The Japanese name for these urchins is tako-no-makura (タコノマクラ), which translates to “octopus’s pillow.” Cute, no?

This banded sea urchin (Echinothrix calamaris) didn't move much either, though the spikey parts waved around, making it difficult to get a clear view of the important areas and action.

I should note that with broadcast spawning, there are usually other individuals of the same species in the reasonable vicinity sending out gametes. Sometimes this takes place at exactly the same time. When that happens, it's pandemonium followed by silence. Miss the relevant few seconds or minutes, and that's it, often until the following year.

In other cases, the casting out of gametes is only roughly synchronised, meaning one goes off here, another there, wait some time and another goes off over there, etc. This makes for a maddening whack-a-mole type situation, where you end up finning from one spot to another, only to see spawning start where you just were, so you rush back that way, just in time to see spawning start where you had just been before you headed back to where you had just been before that. Repeat until no-more-air-too-bad.

This is a Chicoreus ramosus murex shell depositing eggs.

It is a slow process, sometimes spanning days at a time—at least two days in this instance. There were two other murexes of similar size nearby, and one smaller individual as well.

Animals and scenes like this are usually overlooked. They’re not colourful. They’re not charismatic. They don’t “drive engagement” on social media. In short, they fail to titillate.

Which is fine by me, because finding beauty hidden in plain sight is central to my mission in life.

Once deposited, the murex egg casings hang like a chandelier (not sure if this configuration is always the case or not). Individual casings are sort of eggshell-white when fresh, gradually turning light purple, then deeper lavender. Contained within are thousands, probably tens of thousands, of mini-me-murexes.

I referred earlier to species appearing and disappearing. For obvious reasons, I can’t show you current photos of ones that seem to have disappeared from a given area recently, but I can give an example of a species that has shown up in a place outside its traditional range.

This is a pair of bicolor goatfish (Parupeneus barberinoides) spawning:

This species is found throughout warm areas of the Indo-Pacific. Fishbase gives the range as: “Western Pacific: Moluccas and Philippines to western Samoa, north to the Ryukyu Islands, south to New Caledonia and Tonga; Palau, Caroline and Marshall Islands in Micronesia. Recorded from Shark Bay, Western Australia.”

A few years ago, the species made its first appearance in a part of Japan where I’ve invested significant time. The fish is known from waters south of the location, so the move northward is not necessarily big in terms of distance. What probably delineated range was water temperature.

Since the species’ first appearance several years ago, numbers have increased. You can see how in the above photo. Water temperatures have remained consistently high, perhaps giving the resulting young of this species a chance to mature and establish a foothold. I saw multiple younglings this year, testament to this colonisation process.

Another—perhaps more subtle suggestion of changes afoot—is this photograph of a pair of Pharoah cuttlefish (Acanthosepion pharaonis) engaged in reproduction.

The female was ejecting white strands from her siphon just prior to depositing eggs. You can see previous such strands scattered on the substrate.

It took a while to work out what this white stuff might be. In fact, it required consultation with two different malacologists! (Practicing new vocabulary)

The white substance is a gelatinous material females produce in their nidamental glands to envelope eggs. Apparently, females cuttlefishes sometimes eject such material while preparing eggs.

I’ve never seen it happen. No friends that I’ve asked have seen it happen. I could find no reference via online searches, and I was unable to uncover any photos or video of this happening. This species is well-known and documented in Thailand, so I expected that there might be similar sightings there. It seems not. (If you’ve seen this before, please let me know.)

Q: Why does this happen (yet seem to happen infrequently, but happened to such a large extent in this case)?

A: Dunno.

More to the point though, these cuttlefish—which are not seen often in Japanese waters—were a few weeks late compared to when they are normally expected to show up, if they show up.

Remember that I mentioned above that the fat greenlings were late as well? That location is over 2000km north of this cuttlefish location. I can ditto that for other animals this year in locations in between.

On a lighter note, a friend and I found this floating in a shallow bay.

The spongey mass was something like 25cm (8in) long, looking sort of like a puffed-up shower cap.

There were lots of people about, hundreds of divers. No one seemed interested in this floaty-thing of nebulous provenance, perhaps because it was at the shoreline, nestled among assorted flotsam—not the sort of place divers are supposed to be looking for cool stuff.

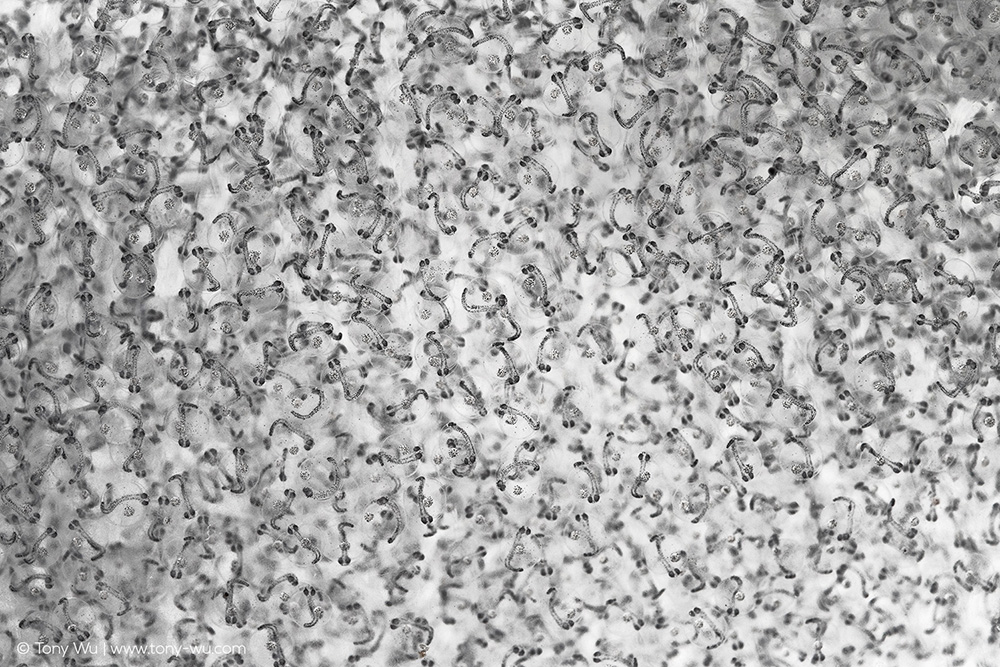

We put it into a large bucket so we could take a closer look. Here is what I saw when I peered through a macro lens:

Yup, developing embryos. Little fishes, complete with eyes, spines and all.

Several weeks later, I managed to ID the floaty thing, thanks to the help of a dive guide I found online and a researcher he’d consulted previously.

Turns out, the inflated shower cap is the egg raft of a giant cuskeel (Spectrunculus grandis). This is a fish you will probably never see, because it is a bathydemersal species, meaning that it lives waaaaaay waaaaaay down deep, like down to 6km (many, many miles), give or take.

The researcher had only documented four previous instances of eggs like this being found. I suspect that the egg rafts are more common around human-places than anyone realises, but the eggs are either ignored or get washed up and dry out.

I imagine that spawning of this species takes place down deep. The egg masses are less dense than seawater, so they float to the surface, where they entrust their fate to the whims of winds, waves and currents (+ occasional storms). When hatchlings emerge, they probably spend some period of time in planktonic stage before making their way down to the abyss.

I found another one the next day, again at the shoreline. I swam them both out as far as I could in hopes of sending them back to open water. Maybe there is a juvenile cusk eel or two out there now as a result.

Finally, in the spirit of the season, let me show you how Christmas tree worms (Spirobranchus giganteus) are made:

In case it’s not obvious, the top one is female, the bottom one male.

What fascinates me about these ubiquitous polychaetes is how and why there are so many colour/ pattern variations in their radioles (fluffy parts). Solid colours like red, yellow and blue are common, but there seems to be an infinite combination of colours and patterns. You can have say 300 on a coral head, and almost all besides the solid-colour individuals will appear to be unique. Maybe that's not the case, but the variety is intriguing.

It's not like there is any camouflage. They stand out. Christmas tree worms are obligate associates of hard corals. The worms get a place to live; the corals apparently get improved circulation, which facilitates feeding. There is some suggestion that the worms provide additional benefits to corals, like warding off crown-of-thorns and helping corals recover from trauma like bleaching. And there might be more than one species. Hard to tell just by looking at their multi-hued rear-ends.

As far as I know, the worm's colours are not due to smaller symbiotic organisms, as is the case for corals.

So why (and how) the riot of colours and patterns?

I spend far too much time contemplating things like this.

That’s it for now. I hope this sampling of the year conveys my deep appreciation for the treasure that is life on Earth, as well as for the privilege that I've had to witness these events and more.

It is now time to rest and relax (aka overeat and sleep).

May you find time during the holidays to reflect upon the good things that have happened, to cherish the special moments, and most importantly, to share, to encourage, to comfort, to love.

ars gratia scientiae

(1) Evolution of Brooding in Sea Anemones: Patterns, Structures, and Taxonomy. Doctoral dissertation 2015, p. 25, Paul G. Larson, Graduate Program in Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology, The Ohio State University

Shareworthy

If you’re looking for something to read during the holidays or next year, take a look at The Social Lives of Animals by Ashley Ward. Dr. Ward is a bona fide scientist who writes like an actual writer, an entertaining one at that. His book is filled with fascinating stories and snippets, as well as fabulous turns of phrase that I wish I’d penned.

His description of mosquitoes: “The Sydney variety is a relentless, questing, sharp-nosed little shit that can drain a human arm or leg to a flaccid, bloodless sausage in moments.” Describing a humpback whale singer: “…he sounded like a pig coming round from a hangover.”

Poetry that is.

I'll leave you to discover his description of naked mole rats for yourself.

Less colourful in vocabulary but just as interesting is Sentient by Jackie Higgins, a book that highlights extraordinary sensory capabilities of certain animals and describes how our own senses relate and compare, often in surprising ways.

In her discussion of the importance of hearing to owls, she quotes another researcher who notes that: “There are plenty of blind animals…But here’s one thing you never find: deaf animals.”

Had to stop and think about that one, consider the reasons why, think through the implications about what senses are truly critical.

I’ll toss-in three more books, somewhat more cerebral, all worth reading:

A Natural History of the Future, Rob Dunn (thanks for the recommendation Maria!)

Other Minds, Peter Godfrey-Smith (picked it up at the Museum of Natural History, London)

Metazoa, Peter Godfrey-Smith

Finally, some links for things to make you go hmmmm:

Isopods that pollinate seaweed

One final photo just for fun, a close-up of a 1cm (0.4in) baby Ezo scallop (Mizuhopecten yessoensis) nestled on the inner surface of a dead bivalve (I think it was an abalone).

Subscribe to my newsletter by email | Subscribe to my blog posts by email