What a week.

Since my last update, we’ve hit 40 ID-ed humpback whale calfs(!!!); re-sighted several babies we previously ID-ed; visited Toku again; been in the midst of a power-packed 8-whale heat run; come across humpbacks with split dorsal fins for the first time this season; been buzzed by a bunch of adorable baby reef sharks; swum among pilot whales; and even had a large pod of spinner dolphins accompany the boat for a good half hour or more.

The weather has finally been cooperative, so we had sunshine, clear skies and calm winds for the entire week. But...the low visibility that’s prevailed for the entire season actually worsened. It seems like there was some sort of mass spawning event around the recent full moon, which basically mucked the water up even more than it already was. Just perfect for underwater photography. Sigh.

Toluono (calf #36, male) relaxing at the surface

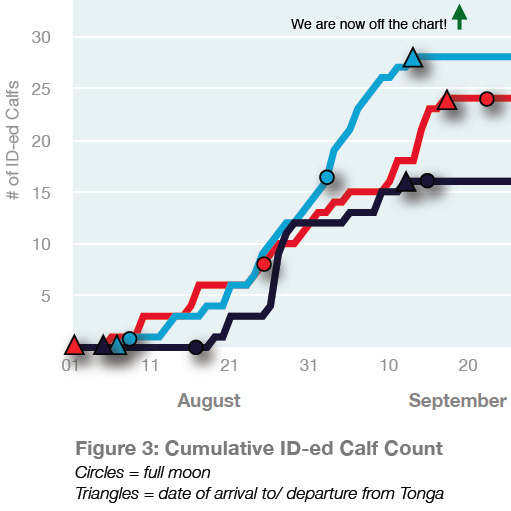

Calf Count

With 40 baby humpback whales ID-ed and counting, we are totally off the chart. I still have nearly two weeks left here, so I’m almost certain the total count will increase.

But by this point in the season, the number of newborns should begin to diminish. In a “normal” season (to the extent such a concept exists), I’d expect that we’d be approaching the tail-end of the birth bell curve, and that from this point forward, the balance of our calf encounters might begin to shift to a greater number of re-sightings, as opposed to new IDs.

This season, however, has proven to be mind-boggling in many respects, so it’s entirely possible that the birth bell curve stretches out for a while more.

In an average season, I’d expect the earliest sightings of newborn humpbacks to occur some time in July, with the latest being in October. This season, the earliest sightings were in late June, i.e., early.

It will be interesting to see if new calf sightings tail off sooner than expected, or if there is no “forward shift”, so to speak, of baby humpback births.

We ended the week with 40 ID-ed humpback whale calfs.

(black = 2008; blue = 2009; red = 2010).

Extracted from my 2010 humpback calf summary.

Also this week, I had my first “calm” encounters with mother/ calf pairs. For most of the season, females with babies have been “neutral” to “skittish”, meaning there have been some, but relatively few, encounters during which mommy humpbacks remained stationary and let their babies swim and play at the surface.

I finally had two such encounters this past week, although only one of the two was truly relaxed...little baby girl Tolunima (calf #35) and her mom.

In the other encounter...with Toluono (calf #36, male)...cow and calf were swimming, but when we entered the water for the first time, the mother skidded to a complete stop and rested at shallow depth, letting the calf explore its surroundings and us...before she arose from her afternoon snooze and continued on her high-pace trek southward.

Finally, we had three re-sightings this week:

- Seventh and eighth sightings of Tahafa (calf #14, male), more about this calf below;

- Second encounter with Tolutaha (calf #31, female);

- Second encounter with Tolufa (calf #34, male).

Tolunima (calf #35, female). This is the first mother/ calf pair I encountered

this season that was stationary while calf played above.

The Little Calf That Could

The star baby of the season has turned out to be Tahafa, the 14th calf we ID-ed. Since my first encounter on 22 August, we’ve come across this little boy whale eight times:

1. 22 August: First encounter, a day after hearing reports of an injured calf, reportedly attacked by a large tiger shark. As soon as I saw the calf, I realised that the stories of a large shark were inaccurate. There was no way the wounds were caused by a tiger or similar animal. The wounds were small, distributed all over the calf’s body, and for the most part shallow. Mother and baby were not particularly friendly, but the baby looked completely healthy.

2. 1 September: Shawn came across this mom and calf, and reported that they were calm and relaxed, a major change since our first sighting, which was a cause for anxiety. There was an escort present. He noted: “Baby seemed feeble and might require extra care. Lacking the spring/ charisma of most calfs. Seemed like the mom had to nose the baby up at the surface. Seemed like the escort understood this and was super respectful of the mom and calf. Sitting below until they came up. Initially, didn’t even know the escort was there.”

3. 2 September: Much to our relief, the baby looked healthy this time, and was quite playful, breaching on several occasions. Still with escort.

4. 3 September: Baby was again playful. Lots of remoras on the baby. Still with escort.

5. 7 September: Mom, baby, escort travelling. Escort breached and tail-slapped. Baby flopped and twirled at surface.

6. 9 September: Still with escort. Baby looking good.

7. 14 September: Found Tahafa with mom and same escort at Toku. Escort fought off multiple male challengers, up to five at a time. Mom and baby relaxed, both very friendly to swimmers. Baby extremely playful and inquisitive. Finally able to determine that Tahafa is male.

At one point in this extended encounter, one of the male whales was singing while swimming. I believe it was the escort, as it was directly beneath me in shallow water, and the sound literally “boomed” through me as I swam. This is not the first time I’ve been in the water when one of several male whales has been singing in an active competitive situation centering upon a mother/ calf pair. It’s not even the first time this season. I’m sure there is something to this. Perhaps it’s a dominance behaviour, intended as a warning to the primary escort’s would-be challengers?

8. 16 September: Sighted Tahafa again at Toku. This time, the escort was gone. We did not attempt to get into the water. Decided to leave mom/ baby alone.

Injured calf Tahafa together with his mother. The baby's wounds have healed nicely.

So over a 26-day period, we’ve documented this injured baby eight times, witnessing the baby’s recovery from wounds due to some sort of traumatic encounter. We’ll probably never know exactly what happened, but one thing is for sure...there was no tiger shark involved.

My preferred guess is an assault by a group of marine mammals (such as pilot whales). Another possible explanation is a run-in with some sort of motorised craft.

In any event, the baby has fully recovered, and the wounds are for the most part healed. In our most recent encounters, Tahafa was unmistakably healthy, energetic and inquisitive...just like a baby whale should be. Hurray!

If we do come across Tahafa again in future seasons, it’ll be easy to ID him from the wounds, especially the missing anterior portion of his dorsal fin.

Escort Enigma

Watching Tahafa’s healing/ recovery process has been fascinating and rewarding, but there’s more to this story...

To start, Tahafa is the first calf that I’ve documented in both Vava’u and Toku, which are about 40km apart. Mom + injured baby (together with escort) swam many kilometres through open ocean, in areas I know are frequented by pack hunters like pilot whales.

This underscores my observation over previous seasons that Vava’u does not seem to be a place where whales stay with their babies.

They may give birth here and/ or visit for some duration. They may even return during a given season, but for the most part, Vava’u is a way station for them, not a permanent home for the season.

Recall also that both the mother and the calf seemed to become relatively calm and relaxed after the escort joined them, sometime between 22 August and 1 September. It’s certainly not the first example I’ve seen of an escort having a soothing effect on mom and baby, but it’s notable in this instance because of the extended period of association.

This is Toluhiva (calf #39, female). Here, the calf is nuzzling the escort,

demonstrating that escort whales can be on good terms with babies

Specifically, the same escort accompanied this mom and calf from at least 1 September to 14 September, over two weeks. Admittedly, I haven’t been meticulous about recording observations pertaining to escort behaviour prior to this season, but this one example illustrates that escorts can and do stay with mother/ calf pairs for extended periods of time.

At this juncture, I have no idea if this particular escort’s behaviour represents the norm here, or if this is an outlying case. But documenting this extended association has given me cause to wonder why escorts even bother accompanying females that already have babies.

The desire to mate would be a logical assumption, one that I’ve taken for granted to date.

But here’s the thing...if moms that show up in Vava’u do regularly mate with escorts (and many moms here seem to be accompanied by escorts), does that imply that those moms have babies in consecutive years?

Consider this possibility for a moment: If a mom mates while she still has a newborn, that would mean that she’d be pregnant while raising that newborn, and would essentially have to face the daunting task of raising a baby while incubating a new baby over the same 12-month period or so.

Then she’d have to return from the south next winter with yearling in tow, part ways with her baby from this season, and then have the next baby soon thereafter...possibly having to go through the whole ordeal again if she’s approached by yet another eager-beaver suitor(s).

I have previously collected data here (Mother of Chibi-chan 200816 same as mother of Floppy 200929; Mother of Scratches 200801 same as mother of Stitches 200904) to suggest that this scenario might be possible (and have also heard from friends in both Hawaii and Japan that there are similar examples there), but you know...it seems like a major undertaking for a female humpback, something that any sane female just wouldn’t want to do...and might not survive if she did.

So even though such behaviour appears to be possible, it seems a stretch to assume that it would be the standard scenario. The energy requirements to feed and raise a newborn + incubate another calf at the same time would be humongous.

Here is an excerpt from a paper that Karen was kind enough to forward to me that addresses this specific issue:

Escorts to mother/ calf pairs on the breeding grounds are invariably male (Glockner-Ferrari & Ferrari, 1985; Medrano et al., 1994), and it has been suggested by Darling, Gibson & Silber (1983) that escorts associate with lactating females in the hope of mating them if they come into post-partum oestrus. However, the high cost of lactation (Lockyer, 1987) makes it likely that a female who is simultaneously pregnant and lactating will be in poorer body condition during the year in which she is nursing the subsequent calf. The percentage of females that we have observed (Clapham & Mayo, 1990) with consecutive-year calves in the Gulf of Maine (a feeding area) was significantly lower than that recorded by Glockner-Ferrari & Ferrari (1985) from the Hawaiian breeding grounds. If this is not entirely due to a bias in sampling towards mothers off Hawaii, the difference may at least partly reflect higher mortality among second calves (those born after an interval of 1 year) prior to arrival in high latitudes. If this is indeed the case, then escorting a mother/ calf pair on the breeding grounds may be a strategy that is inferior to courting or competing for a female who is not currently incurring the expense of lactation.

- Clapham, Phillip J. (1996) The social and reproductive biology of Humpback Whales: an ecological perspective, Mammal Review, 26, 38

This is the escort whale that accompanied Tahafa (calf #14) for at least two weeks

To translate...the paper suggests that for a male humpback to mate with a cow that already has a calf might result in lower probability of his offspring’s survival, and thus not be a wise strategy. This intuitively makes sense.

But if this isn’t the normal situation, then why are so many mother/ calf pairs in Vava’u accompanied by escorts?

So far this season, 20 out of 40 (50%) females with babies we’ve ID-ed have been accompanied by at least one escort. In addition, 11 out of 27 (41%) mother/ calf pair sightings for which we have not established in ID have also involved at least one escort.

One possibility is that the presence of an escort somehow makes it easier for us to approach and ID mother/ calf pairs. I don’t ascribe a high probability to this, however, as the presence of an escort often makes it more difficult to approach females with babies, as I outlined in an earlier post.

Plus, even though I haven’t been tracking escorts in an organised manner during previous seasons, I know from experience that the association of escorts with a significant ratio of females with babies here has always been the case, at least for as long as I’ve been visiting Vava’u.

Of interest, the same paper, on page 40, suggests that the frequency with which males choose to associate with mother/ calf pairs may vary from location to location:

It is curious that, while lactating females are often at the centre of competitive groups in Hawaiian waters (Baker & Herman, 1984b; Glockner-Ferrari & Ferrari, 1990), their occurrence in such groups in the West Indies is far less frequent (Clapham et al., 1992). The absence of calves from most competitive groups in the latter region may reflect a preference by males for females who are not lactating (and are therefore in superior condition). However, why such a phenomenon should apparently not also be observed elsewhere is difficult to understand unless the frequency of post-partum oestrus differs between populations.

Taking this information at face value, it seems like the tendency of males to associate with mother/ calf pairs here resembles the behavioural patterns of humpback populations that visit Hawaii more than of those that frequent the West Indies.

Tahafa's long-term escort. Scraped up dorsal fin...evidence of battle

A Few More Questions, Some Speculation

As I pondered the details of our multiple encounters with Tahafa, mom and escort, a few more issues came to mind.

Why are some escorts (like Tahafa’s) seemingly so loyal (spending at least 14 days by Tahafa’s and mother’s side, including crossing 40km of open ocean and doing battle with five or more aggressive males at a time on multiple occasions) and prepared to undertake bodily risk? (In one particularly spectacular conflict, I watched the primary escort ram nose-first into the belly of another male.)

Another head-scratcher...why, after spending so long with Tahafa and mom, did the escort suddenly disappear by 16 September, less than 48 hours after I had watched the escort engage in serious combat seemingly for the purpose of defending his access to Tahafa’s mom?

And one final twist...when we spotted Tahafa and mom on 16 September, there were dozens of hormone-raged males in the immediate vicinity (like right next to Tahafa and mom), including several that were in hot pursuit of other mother/ calf pairs, and at least seven that were body-slamming one another over bragging rights to what appeared to be a single female.

The question that pops to mind is...if Tahafa’s mom merited so much attention on 14 September (“territorial” aggression by the primary escort + challenges by many other males), then why, less than 48 hours later, was Tahafa’s mom essentially ignored by all the horny males in the area?

I certainly don’t have any definitive answers to these cetacean conundrums, but I’ve pieced together what might be a plausible narrative, one that I can maybe use as an initial framework for developing a better understanding of mother, calf, escort interactions here in the future. It’s pure speculation, trying to fit all the pieces together, but here goes:

What if female humpbacks (whether they are with calf or not) are able to advertise their reproductive status? So let’s say some females with babies go into oestrus while they’re around Vava’u, and they somehow communicate their reproductive readiness to the males in the area (pheromones? audio signals?).

Healthy, happy Tahafa (calf #14) with mom,

primary escort visible in background

Let’s say this takes place some time before she’s actually ready to mate, perhaps up to two weeks.

If Tahafa’s mom sent out just such a signal, and the escort (along with other males) picked up on it back in late August, then there may have been a contest for her acceptance, resulting in the presence of a primary escort with Tahafa’s mom by 1 September (the first time we noted the presence of the primary escort).

From that period forward, the primary may have fended off dozens of challengers, as the female continued to advertise her fertile status.

In this specific example, Tahafa’s mom (and Tahafa for that matter) seemed pleased/ comfortable with the primary escort, so she may not have actively sought to “accept” a different escort, or perhaps she did, but always ended up choosing to associate with the primary escort. In either case, the same primary escort prevailed.

The challenges may have culminated in the all-out assault of multiple males that we witnessed on 14 September, when the primary escort was challenged from left, right, above, below...basically everywhere...by two, three, sometimes five whales at a time, and not always the same whales, meaning the total number of challengers exceeded five.

The reason for the culmination may have been that the time for Tahafa’s mom to mate was near (full moon was two days earlier, on 12 September), and the challengers sensed an opportunity to usurp the primary escort. They could invest a little bit of time and possibly gain the right to mate. If they failed, they wouldn’t have invested too much time, and could quickly move on to something else.

By 16 September, mating was finished. Perhaps the primary escort successfully defended against all challengers and mated.

After that, the primary escort...being male, saw no reason to stick around and left. Other males, sensing no reason to court Tahafa’s mom, diverted their attention to the other receptive females in the area (several with babies, one without).

Tahafa and mom were left in peace...for the first time in several weeks...explaining why the pair were left alone even as wild heat runs and competitive groups coalesced all around them.

Whatever the case, Tahafa, his mom, and the primary escort that accompanied the pair have given me a reason to pay more attention to escorts in future seasons.

If you happen to have any insight into how plausible or not the speculative scenario above might be, please let me know!

Surrounded by humpback whales in a massive, high-energy heat run

Toku Revolutions

Besides the encounters with Tahafa described above, we also had a massive 8-whale heat run at Toku, one that literally took us in circles...around and around and around...as the whales snorted, slapped, smacked, lunged, and dived at high speed.

I’ve seen a lot of heat runs over the years, but this one ranked in the top five or so in terms of energy levels. My friends from the People’s Republic of China who were with me this week couldn’t get enough. Lots of hoots, howls and woohoos! all around.

I also photographed two whales with split dorsal fins there. This is such an unusual trait that I’ve been keeping track of humpbacks I see with dorsals like this, figuring that it’ll be relatively easy to recognise them in the future.

I hadn’t seen any all season (in contrast to five or so I photographed in 2010). Then on 16 September, I photographed two such whales, at the same place, at nearly at the same time. One was the mother of Fanoa (calf #40), and the second was one of the males involved in the big heat run.

One of the whales in the heat run had a split dorsal fin

And just to round out the week, I had a brief visit with a handful of cute baby reef sharks that came to check us out:

One of several baby reef sharks that buzzed us

And then some pilot whales, with a wee little one among them:

Pilot whales in the blue

In case you couldn’t tell, I’m running out of steam and can’t write much more.

My friends from China leave tomorrow, following which, I have several groups arriving from Japan...so I need to catch up on some sleep and recover from the week’s activities.

It’s overcast with a bit of rain today, but I certainly hope the great weather we had last week comes back.

Friends from China, overjoyed with their whale encounters